Bruce Jackson: Cummins Wide

Friday, January 23, 2009–Sunday, May 10, 2009

Installation view of Bruce Jackson: Cummins Wide. Photograph by Tom Loonan.

Photographs from the Arkansas State Prison

Clifton Hall Link

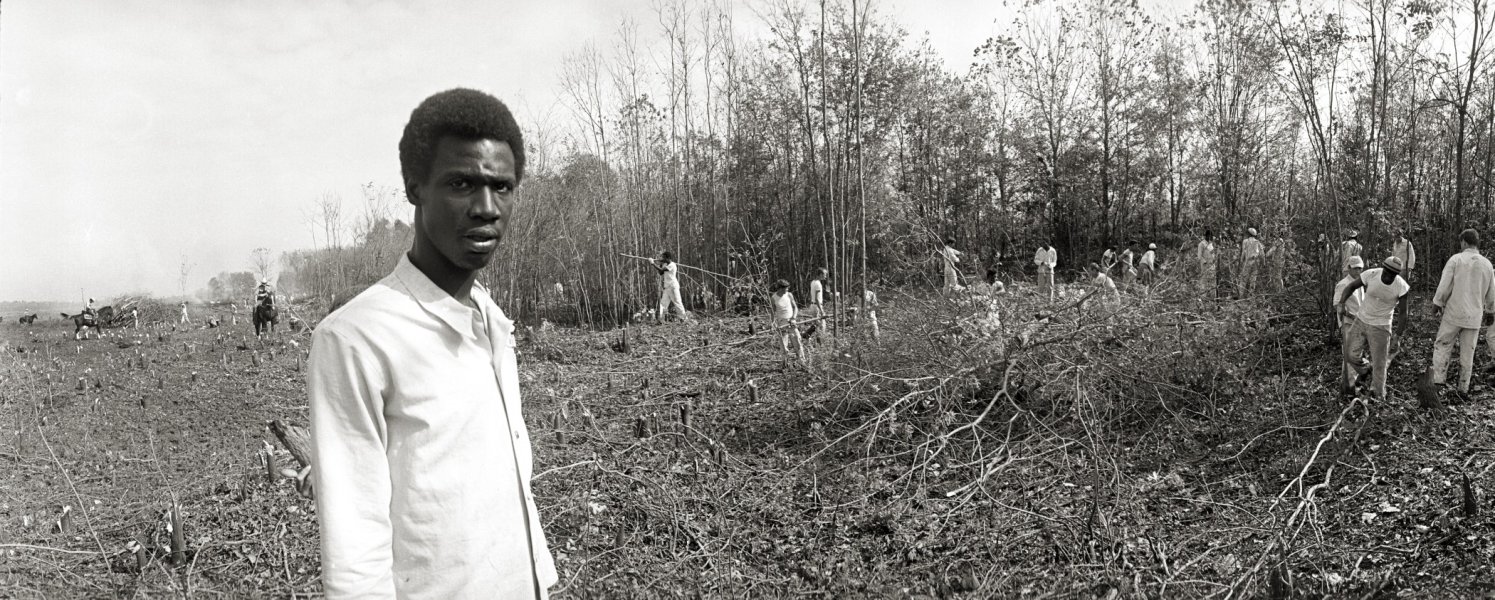

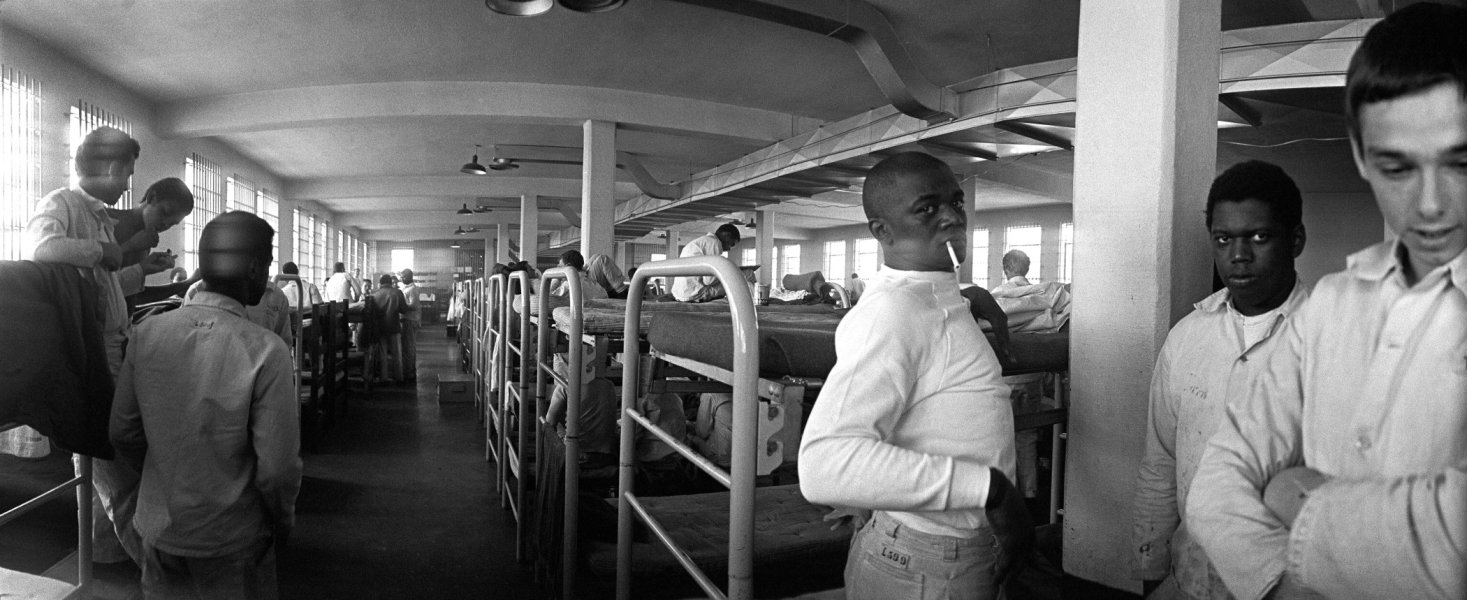

Buffalo-based photographer, filmmaker, and folklorist Bruce Jackson possesses a unique talent to draw us into his photographs and break down the barrier between the viewer and the image. 53 extraordinary Widelux images of Cummins Prison Farm, taken more than 25 years ago, were the focus of this exhibition, which was part of a much larger group of works that included books, film, sound recordings, journal articles, and other photographic exhibitions that center on prison culture in the United States.

Cummins, infamously known in the early 1970s as “the worst prison in the United States,” opened in 1902 and is located in the southeastern portion of Arkansas. The facility spans 16,000 acres, with the capacity to house more than 1,700 prisoners, and is designed to function as a modern-day penal colony commonly known as a “prison farm”—a large correctional facility in which convicts “contribute” to the economy by doing manual labor such as farming and logging in an open-air setting. In 1968, a widely publicized scandal broke at the prison after the skeletons of three inmates, who had allegedly been beaten and secretly buried, surfaced on the farm. The deplorable conditions of Cummins prison were highlighted in a 1971 TIME magazine article where it was referred to as “a virtual slave plantation in the twentieth century” and where “convicts stoop in the vast cotton fields twelve hours a day . . . such are the wages of sin in what may be the nation’s most Calvinistic state.”(1) Following this incident, a federal judge found the conditions of the Arkansas State Penitentiary System so poor that he deemed the Cummins facility unconstitutional and placed it under federal protection.

Prompted by curiosity, Jackson visited Cummins prison in 1971, shortly after the scandal broke, while on his way to San Francisco from Buffalo. During his initial visit to Cummins, Jackson shot nine rolls of film. A year later, he visited again, and shot 29 additional rolls of film. Intrigued by the changes that had occurred within the prison between his first two visits, he visited six more times and took a staggering 4,000 photographs. While the majority of images Jackson took were with Nikon F2 35mm cameras, on his last two visits he incorporated a Leica M4 and a Widelux F6B. The images taken with the Widelux camera are the most distinctive and impart a poignancy that is both filmic and straightforward. First developed in Japan in 1948 for both 35mm and medium-format models, the Widelux is a fully mechanical swing-lens panoramic camera with a 26mm lens that pivots on an axis. This unique pivoting lens allows the photographer to capture a panoramic view that is not available with traditional cameras. The Widelux field of vision extends beyond the realm of human sight, bringing into clarity that which is blurred in our peripheral vision and that which we are “never capable of seeing” unless we turn our head and refocus our perspective.

In this presentation of the series, Jackson juxtaposes interior and exterior views to create a compelling narrative of life within the confines of Cummins prison during a pivotal time. Today, social perceptions of life behind bars are oddly romanticized through a warped perspective culled from the media’s portrayal of such realities. With a rise in popular television series that portray “prison life” from either a fictional or documentary standpoint, such as the popular HBO drama Oz, or MSNBC’s documentary series Lockup, which “investigates what goes on behind the bars, and inside the minds of prisoners and guards,” Americans are steadfastly gripped by their morbid fascination with the social underbelly. As reform in American prisons is persistently a topic of debate, Jackson’s timeless, haunting images continue to narrate a flawed system amidst a society where crime continues to rise and our nation’s crowded prisons linger on the periphery of chaos.

This exhibition was organized by Associate Curator Holly E. Hughes.

(1) "The Shame of the Prisons,” TIME (January 18, 1971).