Figuratively Speaking: Sculpture from the Collection

Friday, November 30, 2007–Sunday, March 2, 2008

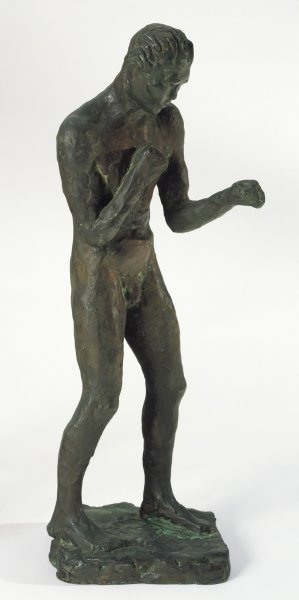

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (French, 1841–1919). Small Standing Venus, 1913. Bronze, 23 1/2 x 12 1/8 x 8 1/8 inches (59.7 x 30.8 x 20.6 cm). Collection Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, New York; James G. Forsyth and Sherman S. Jewett Funds, 1947 (1947:1).

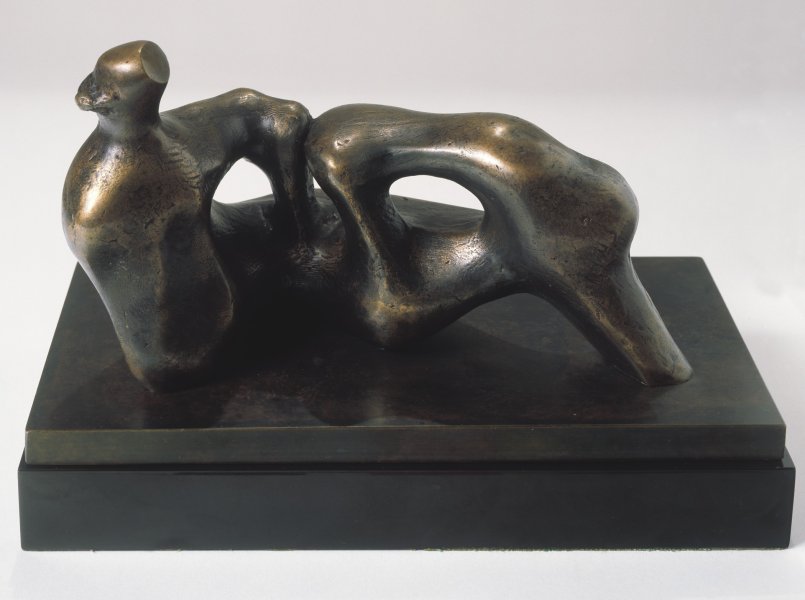

Through an ongoing collaboration, this exhibition brought together works from both the Albright-Knox's collection and the Buffalo Museum of Science, exploring a multitude of approaches to the sculpted human form.

Art is not the application of a canon of beauty, but what the instinct and the brain can conceive beyond any canon. When we love a woman, we don't start measuring her limbs.

— Pablo Picasso

Throughout time, the human body has served as an innate subject for sculptors given the various opportunities it offers for exploring nature’s beauty. Although Paleolithic depictions of the female figure are among the earliest examples of the body in sculpted form, it became a salient subject with the emergence of a canonical approach to making art during Dynastic rule in ancient Egypt. While new methods at times evolved the established style, throughout 3,000 years of Egyptian history artistic modes of representing the human figure remained essentially the same. The established style, which manifested as a means to honor preeminent rule, reflects a beauty that is highly stylized and symbolic. With changing times and cultures, the development of the human figure progressed in Greek and Roman sculpture, as did a naturalistic style that eclipsed that which came before. Figurative representation became more free flowing and true to life—a style that would later seek reverence in post-Medieval Europe in the form of Classicism.

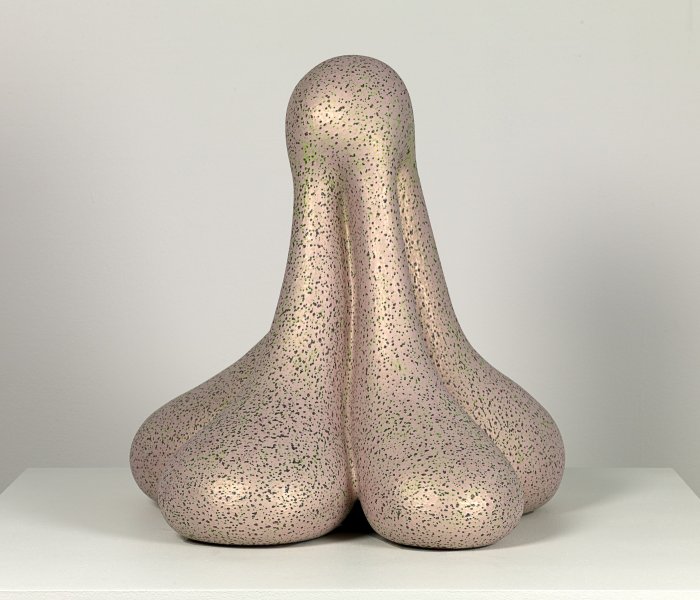

Beginning in the 20th century, however, artistic approaches to the figure recede from empathetic presentations of the body to a shift in form and visual dialect. This shift began to cultivate a relationship with the viewer that signaled the sculptural body as both experiential and confrontational. The arena from which artists cultivated inspiration also expanded, in turn opening our eyes to life outside the Western European canon to help better understand that figurative “art” does not always imply a majestic reclining nude, fetishized Venus, or regal bust. Many of the works in this exhibition present the body in a highly representational, intimate scale, while others employ more artistic license as parts of the figure morph into simplistic shapes devoid of the minutiae that makes us distinct. Nevertheless, while literal representation is frequently achieved, it is often not the primary goal of an object.

This exhibition was organized by Associate Curator Holly E. Hughes.