On the occasion of Women’s History Month, and in conjunction with the National Museum of Women in the Arts’ fourth annual #5WomenArtists campaign, we're highlighting five women artists with works in our collection each Wednesday this month. This week we focus on artists who have participated in our Voices in Contemporary Art Lecture Series.

Aria Dean is an artist, critic, and curator whose work examines the frameworks of our individual and collective identities. She is particularly interested in the complicated relationship between “blackness” and the internet, which has created new platforms for the creation and consumption of culture. The first solo museum presentation of Dean’s work included three videos that explore how blackness is constructed through the repetition and circulation of its representations. Making references to pop culture, philosophical texts, and her own family history, these works are part of Dean’s contributions to a larger conversation on the social effects of new technologies. Dean recently gave a Voices in Contemporary Art talk on January 10.

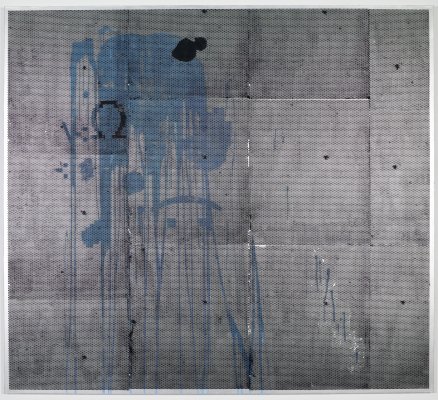

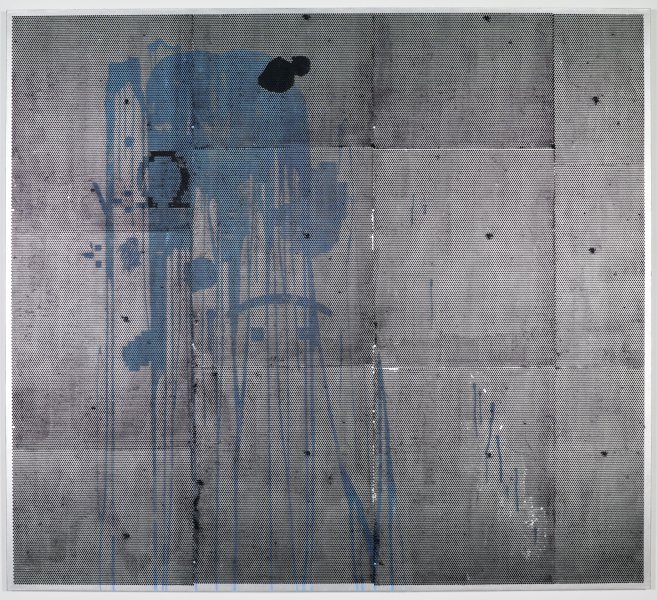

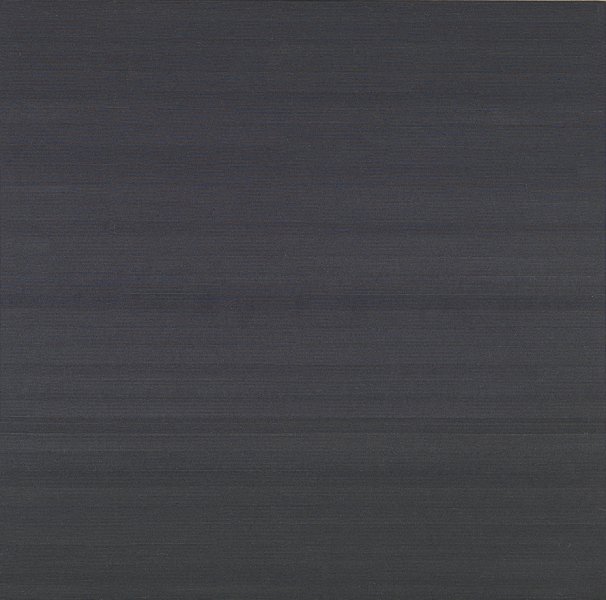

Jacqueline Humphries's One Cat, 2017, hails from a body of work that she began around 2015 in which she explores the relationship between visual culture in the digital sphere and the central problems of analog abstract painting. Earlier in her career, Humphries engaged with the grid and drips as characteristic elements of this tradition in works like Hit or Miss and Black Dog, also in the Albright-Knox’s collection. However, more recently she explained that “I really wanted to engage this aspect of our life with screens—how much time we spend looking at these little teeny things on our phones when there’s this big world out there.” Humphries will discuss her work in a Voices in Contemporary Art talk with Chief Curator Cathleen Chaffee on March 14.

From the beginning of her career, Liza Lou has been drawn to the historical uses of beads and their potential to create, as the artist has described, “an art with a starting point of zero, art that grows up not knowing it’s art at all.” In 2002 she received a grant from the MacArthur Foundation, which allowed her to move her studio from Los Angeles to Durban, South Africa. There she immersed herself in the long cultural tradition of beadwork among the Zulu, Xhosa, and Ndebele people, an experience that fundamentally transformed her understanding of the medium. Lou recently discussed her work Carbon / Solid, 2012–14, during a Voices in Contemporary Art talk on February 21.

In early 1971, Dindga McCannon, Kay Brown, and Faith Ringgold gathered a group of black women at McCannon’s Brooklyn home to discuss their common frustrations in trying to build their careers as artists. Not only did they find that juggling their creative ambitions with their roles as mothers and working heads of households left little time to make and promote their art, but they also felt excluded from the largely white downtown art world as well as from the male-dominated black art world. Out of this initial gathering came one of the first exhibitions of professional black women artists: “Where We At”—Black Women Artists, 1971. McCannon's Revolutionary Sister, 1971, was on view in We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women, 1965–85 in 2018; the artist gave a Voices in Contemporary Art talk on February 16, 2018.

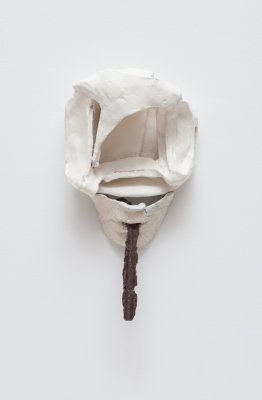

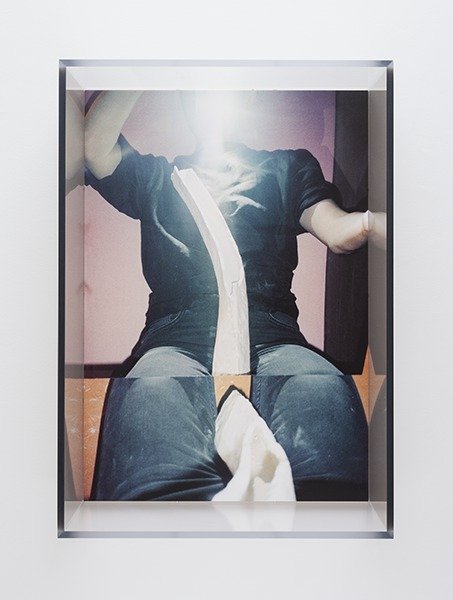

B. Ingrid Olson creates highly personal photographs and sculptural reliefs that push back against traditional modes of artmaking. Within the confines of her studio, she records her body as it shifts and relates to its surroundings. The results of this dynamic process are multidimensional objects that capture the world as seen through the eyes of an artist. In 2018, Olson created a site-specific installation, B. Ingrid Olson: Forehead and Brain, that uniquely engaged the Albright-Knox's Gallery for Small Sculpture. The Chicago-based artist discussed her practice with Godin-Spaulding Curator & Curator for the Collection Holly E. Hughes in a Voices in Contemporary Art talk on May 17, 2018.