On the occasion of Women’s History Month, and in conjunction with the National Museum of Women in the Arts’ second annual #5WomenArtists campaign, we're highlighting five women artists with works in our collection each Wednesday this month. This week we focus on artists who were active in the 1950s, ’60s, ’70s, and beyond.

Helen Frankenthaler’s soak-stain technique involved thinning paint with turpentine and pouring it onto bare canvas, allowing it to fuse with the surface in ways only partially under her control. In 2014–2015, the Albright-Knox organized Giving up One's Mark: Helen Frankenthaler in the 1960s and 1970s, which focused on Frankenthaler’s transition from oil to acrylic paint, and from gestural abstraction to robust images of consolidated color and tonal nuance. Frankenthaler’s Tutti-Fruitti, 1966, is currently on view in the 1962 Building.

A highly self-critical artist given to regular, periodic editing of her work, Lee Krasner began in 1952–53 to destroy a group of paintings that she wished to reject. The process of unstretching and cutting up the canvas suggested the idea for a series of collages made from resulting fragments. The Albright-Knox’s Milkweed, 1955, likely resulted from this process. This work was recently featured in The Long Curve: 150 Years of Visionary Collecting at the Albright-Knox Art Gallery (2011–2012).

When Joan Mitchell settled in New York in 1950, she abandoned representation entirely and turned to painting abstractions, creating works that reflect the people, places, and experiences that made up her life. The Albright-Knox’s George Went Swimming at Barnes Hole, but It Got Too Cold, 1957, refers to her poodle, George, whom she loved deeply, and often went swimming with. It was first shown at the Albright-Knox in Contemporary Art: Acquisitions 1957–1958 just a year after it was created.

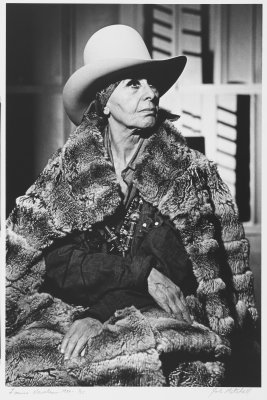

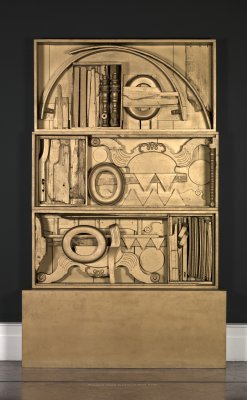

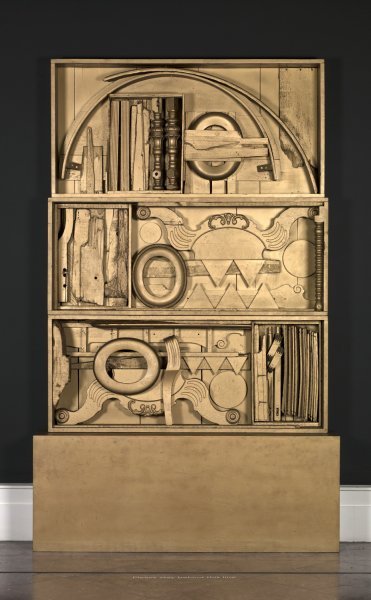

Louise Nevelson studied with Hans Hofmann and worked as a mural assistant to Diego Rivera. During the 1950s, she developed her wood constructions, largely composed of found objects, the first of which were painted matte black, followed by a series in metallic gold paint, and another in white. She also made sculptures in metal and from Plexiglas. The Albright-Knox owns 23 works by Nevelson, including Royal Game I, 1961, which was most recently on view in 2016’s For the Love of Things: Still Life.

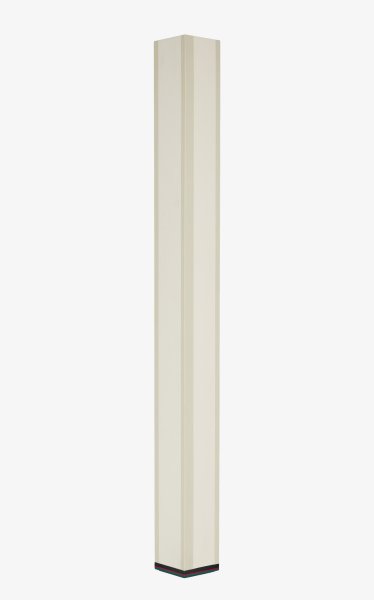

The Albright-Knox owns seven of Anne Truitt’s signature painted wood columns. In 1977, Truitt stated that her ultimate goal was to achieve “color in three dimensions, color set free, to a point where, theoretically, the support should dissolve into pure color.” The museum acquired Truitt’s Sentinel, 1978, in 1980, and six more sculptures in 2008 as part of the Panza Collection. The works were on view in 2007–2008’s The Panza Collection: An Experience of Color and Light and, more recently, in 2016’s Defining Sculpture.