On the occasion of Women’s History Month, and in conjunction with the National Museum of Women in the Arts’ third annual #5WomenArtists campaign, we're highlighting five women artists with works in our collection each Wednesday this month. This week we focus on artists whose works are included in our current exhibition Window to Wall: Art from Architecture.

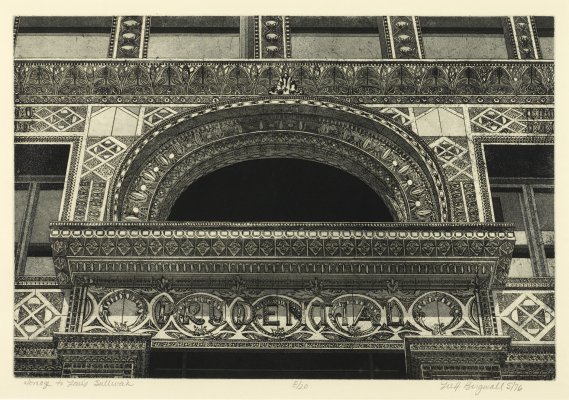

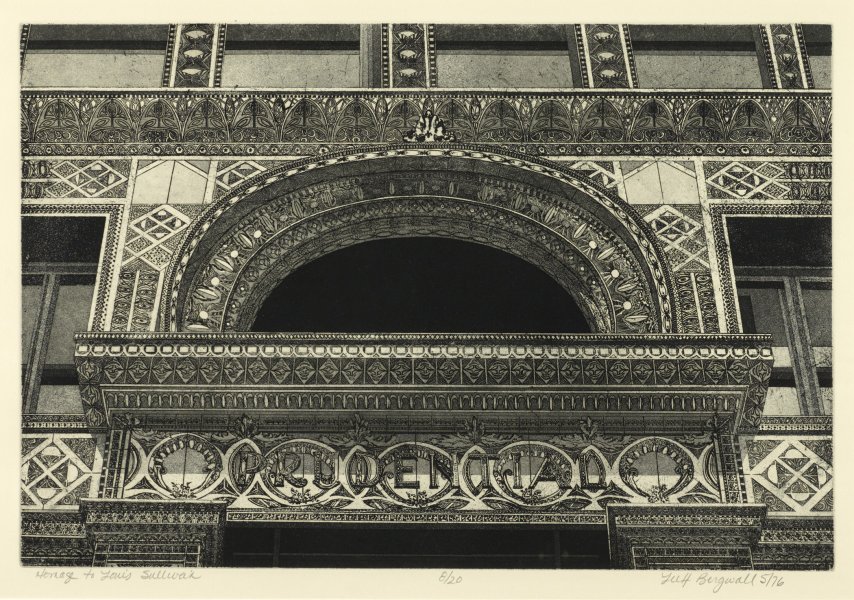

Buffalo native Lee Bergwall Hanks received her MFA in printmaking from the University at Buffalo in 1977. Made while she was a student, Homage to Louis Sullivan, 1976, positions us standing on the sidewalk and looking up, as if in awe, at Louis Sullivan's 1895 Guaranty Building, located at 140 Pearl Street in downtown Buffalo. Through her controlled etching, Hanks replicates the building's intricate ornamental pattern, covering the surface of her design with marks just as Sullivan covered the skyscraper with tiles.

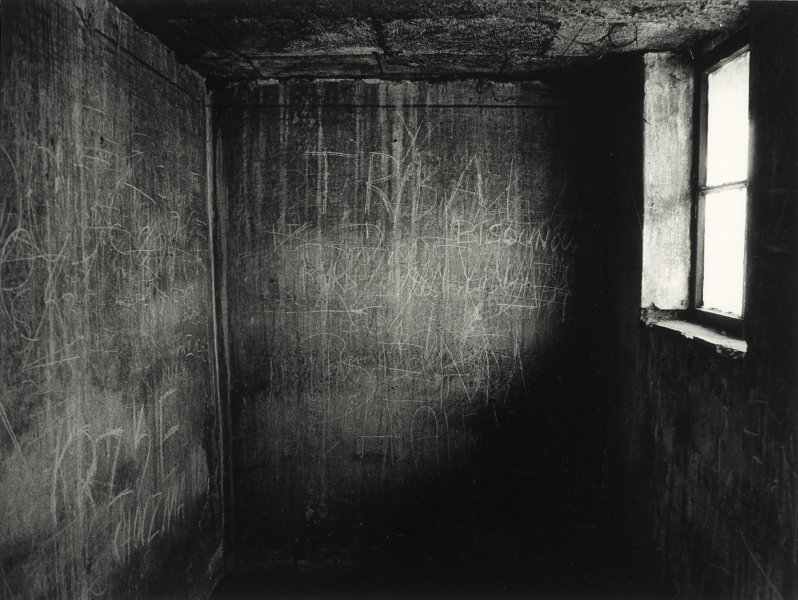

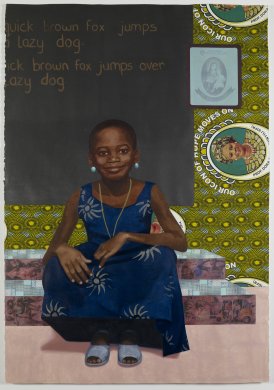

While our collective memory of the Holocaust risks becoming more distant with the passage of time, Judy Glickman Lauder’s photographs of Auschwitz use artistic techniques to insist that we continue to look. With their blurry focus and stark contrasts of light and dark, they convey a sense of drama equal to the emotional charge of their content. In Lauder’s images of one of the most evil structures ever built by man, architecture is far from a neutral backdrop to history: it can be an agent of terror, but also of memory and empathy.

Joyce Kozloff was one of the original members of the Pattern and Decoration movement, as well as a figure in the feminist art movement of the 1970s. Her early work focused on patterns and their cultural significance, while much of her later work utilizes mapping as a device to explore her interests in history, culture, and the decorative and popular arts. Kozloff's Untitled (Buffalo Architectural Themes), 1984, is on view in Window to Wall.

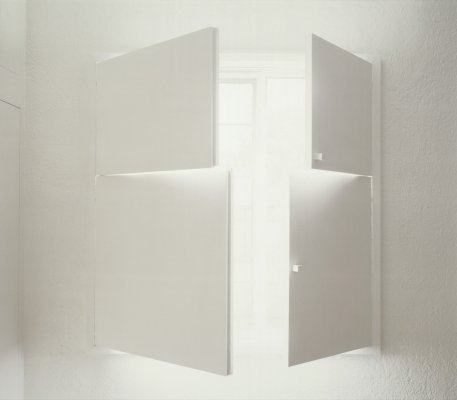

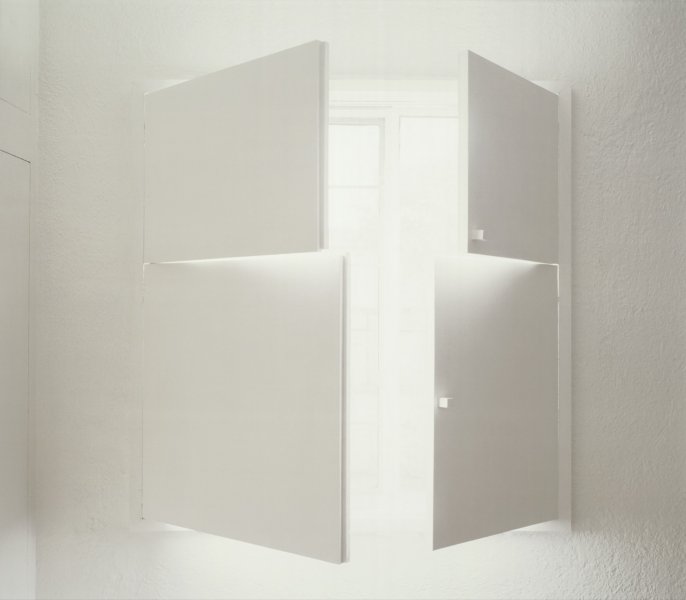

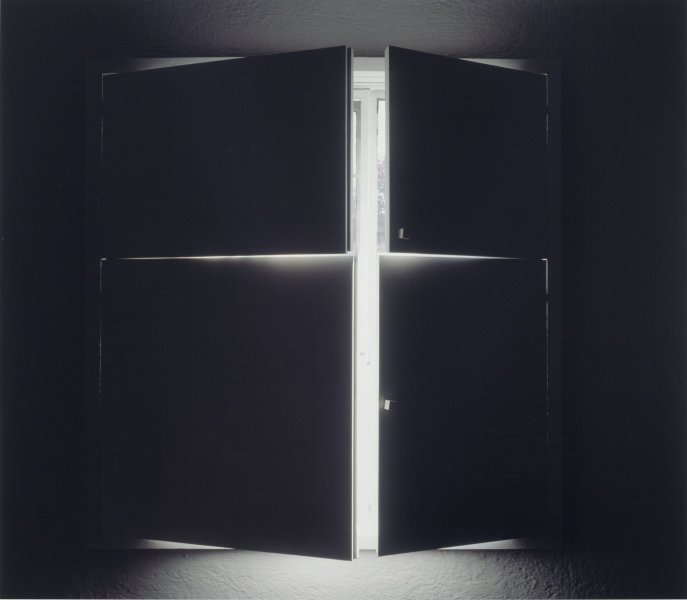

Luisa Lambri’s photographs, which feature buildings designed by famous architects, offer us intimate views of specific details. The Albright-Knox owns two images of a window in the home of Mexican architect Luis Barragán—both of which are on view in Window to Wall—and six images of a window in the Darwin D. Martin House, designed by Frank Lloyd Wright. As Lambri explained in 2014, her photographs are byproducts of her physical interactions with buildings, allowing her to interject her own perspective into the (traditionally masculine) history of architecture.

Rachel Whiteread makes sculptures by casting various objects designated obsolete and destroyed in the name of progress, including furniture, staircases, water towers, and even an entire house. Uselessly propped up against the wall, Doorway I, 2010, may remind us of a collapsing structure and, more broadly, of all the homes we’ve lost or left behind. It insists that the architectural elements that shape our lives—including even those as humble as a nondescript door—can be conduits of personal and cultural memory.