“Sculpture Exhibition-Entire file destroyed by Mrs. Q-remainder in this folder.”

This enigmatic label, found amongst the exhibition files, contradicts the extravagant public display of sculpture during the Exhibition of Contemporary American Sculpture in 1916. This exhibit featured more than 800 works of sculpture, represented 168 contemporary American sculptors, and extended beyond the Albright Art Gallery’s campus into Delaware Park and parts of Elmwood Avenue.

Karl Bitter, President of the National Sculpture Society, first proposed the idea of arranging an exhibit of American Sculpture in a letter written to Charles Kurtz, the first director of the Albright Art Gallery in 1907. Due to Kurtz’s untimely death in 1909 and Bitter’s death in 1915, this exhibit wasn’t realized until 1916. Cornelia Bentley Sage Quinton, who established her tenure after Kurtz, organized this exhibit with Karl Bitter. After Bitter’s death, Mr. Herbert Adams, the newly elected President of the National Sculpture Society, and a committee of sculptors worked with Cornelia to finally bring this exhibition to life.

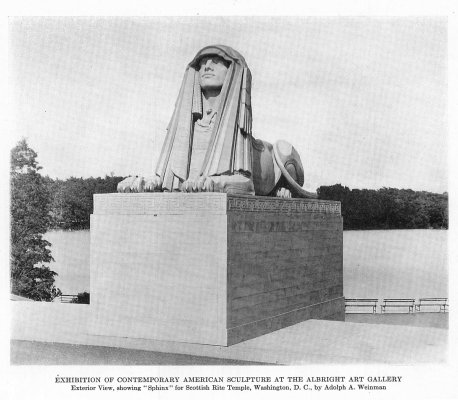

One of the highlights was Daniel Chester French’s Spirit of Life: Spencer Trask Memorial, 1914, a majestic sculpture that was the central focus of the garden pool placed in the Sculpture Court. The Sphinx, 1915, by Adolph Alexander Weinman can be found today at the the House of the Temple (16th Street Freemasons Temple) in Washington, D.C. Hermon Atkins MacNeil gifted the large plaster cast of Washington in 1916, but unfortunately weather conditions caused the sculpture to deteriorate so it had to be destroyed.

It remains evident that Contemporary American Sculpture heightened the Albright Art Gallery as an international symbol of artistic potential, so why did “Mrs. Q” destroy this file? One possibility may be due to Cornelia’s involvement as a French activist during the outbreak of World War I. The sensitive correspondence between French artists and friends could have prompted Cornelia to destroy these confidential records. Why leave such a statement behind? Questions will continue to arise, but for now, the destruction of this file will remain one of the many mysteries in the archives.