As art historians, we’re taught to think of provenance, or ownership history, as a key facet of the “life” of an artwork. When an artist releases their work into the world, its journey is largely determined by the people who hold and care for it. Practices of art collecting and ownership are also indelibly fused to histories of conflict and global power dynamics. As our shared recognition of this relationship has grown in recent decades, cultural institutions around the world have dedicated more time and resources to researching the provenance of their collections. This research is not only helpful for contextualizing and interpreting objects—it is a necessary act of legal and ethical accountability.

As art historians, we’re taught to think of provenance, or ownership history, as a key facet of the “life” of an artwork. When an artist releases their work into the world, its journey is largely determined by the people who hold and care for it. Practices of art collecting and ownership are also indelibly fused to histories of conflict and global power dynamics. As our shared recognition of this relationship has grown in recent decades, cultural institutions around the world have dedicated more time and resources to researching the provenance of their collections. This research is not only helpful for contextualizing and interpreting objects—it is a necessary act of legal and ethical accountability.

In August of 2022, New York State Governor Kathy Hochul signed Senate Bill S117A into law, which requires museums to display prominent signage disclosing any objects on view that were looted, sold under duress, or confiscated by the Nazi regime in Europe. In keeping with the law and in preparation for the Buffalo AKG Art Museum’s grand reopening, I began an extensive review of works in the permanent collection that were created before 1945 and changed hands in Europe between 1933 and 1945. My research confirmed much of what we already knew. Two of our masterworks, Le Christ jaune (The Yellow Christ) by Paul Gauguin and Mlle Fiocre dans le ballet "La Source" (Mademoiselle Fiocre in the ballet "La Source") by Edgar Degas, were indeed looted by the Nazis following their invasion of France. In both cases, the paintings were recovered and returned to their rightful owners before they entered our permanent collection. These resolutions are more fortunate than many others from the period.

I felt a sense of relief with each verification, but I also began to notice “close calls”—artworks that changed hands at an opportune moment and were spared from Nazi interference as a result, while the previous owners suffered in the months and years to follow. The provenance of one painting in particular stood out to me as the most chilling example: Franz Marc’s Die Wölfe (Balkankrieg) [The Wolves (Balkan War)], 1913, of which no less than three previous owners fell victim to the depredations of the Nazis and the ravages of war.

Franz Marc (German, 1880–1916) painted The Wolves in response to a series of armed conflicts in the Balkan states that contributed to the eruption of World War I just one year later. The tension and volatility of that time caused a dramatic shift in Marc’s visual language, from his early mystical landscapes—works that signaled a gentle spirit and an admiration of nature—to darker premonitions of destruction and chaos. The Wolves is an arresting image rendered in electric shades of red, yellow, green, and blue, all punctuated by blackened geometric shapes that explode across the canvas like hot shrapnel. A pack of wolves march through the razed landscape with mechanical postures and vacant expressions. Several bodies lie motionless in the field, soon to be reclaimed by the Earth. This representation of death evokes an odd serenity that could even be mistaken for sleep. Two flowers wilt in the foreground, a suggestion of withering hope for mankind and nature. This depiction of war conspicuously lacks sides, holding the apparent loss of life in sharp relief. In hindsight, The Wolves reads like a grim foretelling of the artist’s own future. Marc experienced the horrors of World War I firsthand, where he fought as a cavalryman for the German army until his death in 1916 at the exceptionally deadly Battle of Verdun. It would appear that violence was destined to follow The Wolves from its creation.

By 1914, while facing the near certainty of war on a mass scale, Marc adopted a paradoxical belief that the impending brutality offered a chance for societal rebirth. He dreamt of a new artistic and philosophical age driven by creative experimentation, innovation, and peace. Variants of this belief grew popular in the European avant-garde circles that included Marc and his contemporaries, with some leaning more heavily into an affinity for war and even fascism. In Berlin, modern art was championed at Galerie Der Sturm, an exhibition space founded in 1912 after a prolific avant-garde magazine by the same name. Der Sturm fostered a robust international creative scene by welcoming artists from a variety of movements such as the Fauvists, Cubists, Futurists, Suprematists, Expressionists, and more. In August of 1913, Marc brought his recently completed work The Wolves to Der Sturm where it was acquired by the gallery’s founder, Herwarth Walden.

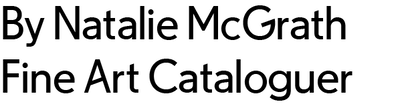

Walden (German, 1879–1941), born Georg Lewin in Berlin, demonstrated an advanced creative aptitude from an early age through his studies of music and literature. Der Sturm, as both a publication and a gallery, became his crowning achievement, positioning him as a key cross-disciplinary figure in the history of German Expressionism. Walden relinquished his given name in favor of the pseudonym invented by his first wife, the German Expressionist poet Else Lasker-Schüler (1869–1945), in reference to Henry Thoreau’s book Walden, or Life in the Woods (1854).

After holding The Wolves for several years, Walden sold the painting to an avid collector of modern art by the name of Heinrich Kirchhoff before closing Der Sturm in 1932 just one year before the Nazis rose to power. Walden’s Jewish heritage, his alignment with the German Communist Party, and his dedication to what would soon be considered “Degenerate Art” made him a target for Nazi persecution. Having placed the remainder of his art collection with his second wife, Nell (née Roslund, Swedish, 1887–1975), Walden fled Berlin for the Soviet Union—a choice that would prove to be a grave miscalculation. While continuing his work in publishing and scholarship there, Walden fell under the scrutiny of Stalin’s government due to the regime’s xenophobia and associations of the avant-garde with fascism (à la the Italian Futurists). By 1941, as the chaos depicted in The Wolves took on new meaning in the active devastation of Europe and the Pacific in World War II, Herwarth Walden disappeared into the gulag. His death was confirmed by his daughter twenty-five years later, in 1966.

Back in 1932, The Wolves left the care of Herwarth Walden and entered the formidable collection of Heinrich Kirchhoff (German, 1874–1934). In 1908, Kirchhoff had moved to the town of Wiesbaden and immediately began constructing a picturesque villa for his own residence as well as a retreat for artists, complete with studio spaces and lush gardens for inspiration. Kirchhoff began collecting German Impressionist art around this time, and his tastes gradually shifted towards Expressionism and abstraction, greatly favoring Franz Marc and his contemporaries in due course. Kirchhoff became known as a consummate patron of the arts, not only inviting artists to live and work at his estate but also regularly loaning his collection to the Museum Wiesbaden for the public to enjoy. This utopic arrangement would not last, however, as political tensions eventually pushed the Kirchhoff family to pull the collection from view. The esteemed collector died in 1934, presumably of natural causes, and his collection was gradually sold by his surviving family. Kirchhoff’s home and beloved gardens were claimed by the war.

After Wiesbaden, The Wolves was acquired and briefly held by a Ms. M. Kruss, most likely the first wife of Markus Kruss, a German Expressionist art collector and business partner to the Zuntz family of coffee merchants. By 1936, Kruss had either sold or gifted the painting to August Zuntz, head of the family’s business operations in Berlin who shared a similar affinity for collecting avant-garde art. The Zuntz family’s beginnings in the coffee industry date back to the eighteenth century, and the trajectory of their success is the stuff of legend. Over the course of several generations, their company, A. Zuntz sel. Wwe., grew from a struggling grocery shop to a household name across Germany, and even became the official coffee supplier for the Imperial Court in 1893. The company was also known for opening many of the first quick-service coffee shops of its time—a convenience that we consider indispensable today. Unfortunately, the Zuntz family fell victim to the Nazis’ predatory “Aryanization” policies, or the confiscation and transfer of Jewish-owned properties and businesses to non-Jews. This process was carried out in stages: the first of which was considered “voluntary,” as Jewish-owned businesses that had been starved out by Nazi propaganda and boycotts were gradually sold, often at a fraction of their true value. The second stage was undeniably forced, as new laws required any remaining Jewish business owners to be dispossessed of their property. Shortly after A. Zuntz sel. Wwe. was seized, August Zuntz and a very few of his family members escaped to England with their lives and their remaining possessions, including The Wolves. We now know that the Zuntz family regained the company and attempted to resume operations after the war with the help of Markus Kruss, but business unfortunately never returned to its pre-war state. A Zuntz sel. Wwe. operated under the family’s leadership in its diminished capacity until it was sold in the late 1970s. As for The Wolves, our records indicate that the Zuntz family held the painting for many years in London until they made the acquaintance of Dr. Grete Ring, director of the art dealing firm Paul Cassirer, Ltd. Through this connection, the Zuntz family sold The Wolves to Dr. Walter Feilchenfeldt, another associate of the firm who had also fled Berlin to escape Nazi persecution. Shortly after his purchase, Dr. Feilchenfeldt connected with Curt Valentin of Buchholz Gallery in New York City to facilitate the sale of The Wolves to our collection, then known simply as the Albright Art Gallery.

While conducting this provenance research, I was repeatedly struck with disbelief over the journey that this painting has taken, dodging theft and destruction at multiple turns to cross the ocean and find its home here in Buffalo. Now, many exhibitions and two museum expansions later, the painting occupies the Robert and Elizabeth Wilmers building, in the absolute best of company. The Wolves currently shares a gallery with other groundbreaking works by Pablo Picasso, Francis Picabia, Sonia Delaunay and Blaise Cendrars, Constantin Brancusi, Georgia O’Keeffe, Robert Delaunay, František Kupka, Vassily Kandinsky, and Marsden Hartley—all visionaries of the early twentieth century who pushed abstraction to its limits and radically redefined art for subsequent generations of makers. Histories like that of The Wolves remind us that the works in our galleries have seen tragedies and triumphs beyond our reckoning. When we learn the stories behind great works of art, we become attuned to the truths they speak across time, woven into each piece as tightly as canvas fibers.

About the Author

Natalie McGrath has worked with the Buffalo AKG Art Museum for nearly three years, first as a Curatorial Intern in 2018, and now as the museum’s Fine Art Cataloger since early 2021. McGrath maintains the museum’s Fine Art Collection database, assists staff and researchers with information requests regarding the Fine Art Collection, and sources essential documentation for new and existing artwork records. McGrath holds a BA in English from the State University of New York at Buffalo, and an MA in art history from Syracuse University.