By Ava Danieu

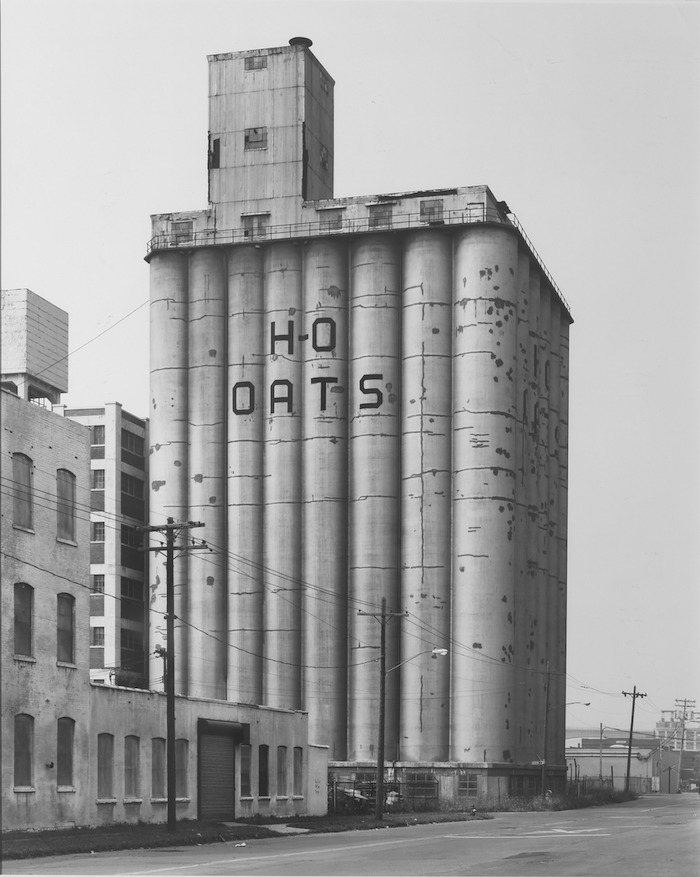

Soaring and dilapidated concrete grain elevators dot the shoreline along the Buffalo River, reminding the city of its storied economic past.

In 1825, the completion of the Erie Canal allowed midwestern farmers to ship products to the Port of New York, drastically reducing the shipping journey from 3,000 to 450 miles. [1] With goods arriving by boat, the steam-powered grain elevator could store up to 47 million bushels, cementing Buffalo’s role as a hub in the food distribution chain. [2] From 1850 to 1950, Buffalo was the largest grain port in the world. Nearby and close to the city center, livestock were butchered and traded at the Chippewa/Washington market, which was founded in 1865. [3] From conspicuous livestock butchering to towering grain elevators, food systems were highly visible to the early twentieth-century Buffalonian.

After World War II, American food systems shifted away from the consumer’s view. In Buffalo, grain storage declined, with the last grain elevator built in 1954. [4] Reflecting on the changing landscape of food systems nationally, Dr. Samina Raja from the Food Systems Planning and Healthy Communities Lab at the University at Buffalo writes:

First, suburbanization of the American landscape physically distanced consumers, farmers, food processors, and others involved in the food trade, rendering the notion of a linked and spatial food system irrelevant. Second, significant advances in food technologies used to process and package foods resulted in the production and widespread prevalence of food products that bore little resemblance to their source plant or animal, rendering food’s origins — and indeed the entire system that moved food from farm to table — nearly invisible. [5]

Scholars, urban planners, and community activists have been examining the physical distance and invisibility in American food systems for years, but these issues are also providing fruitful grounds for recent artistic intervention. The ongoing exhibition Narsiso Martinez: From These Hands/De Estas Manos at the Buffalo AKG Art Museum interrogates working conditions in the fruit fields of the western United States.

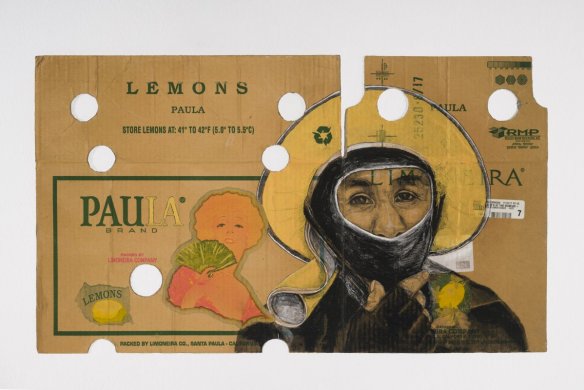

The artist Narsiso Martinez was born in Oaxaca, Mexico, then moved to Los Angeles in 1997 at the age of twenty. Upon settling in the United States, Martinez was determined to pursue a formal education. He picked produce in the fields of eastern Washington to help pay for his education. After graduating from college, he returned to the produce fields with his art supplies and used a Costco box to create studies of farmworkers. [6] Martinez recounts frustrations with the traditional canvas while in art school at California State University, Long Beach. In a critique, his classmates supported his use of cardboard, prompting him to collect boxes from friends who work at grocery stores. [7] These assemblages bring salvaged materials into new arrangements with social potential, similar to the Los Angeles-based artist Noah Purifoy. Both Purifoy and Martinez use collected debris to form artworks that interrogate and undermine dominant class structures.

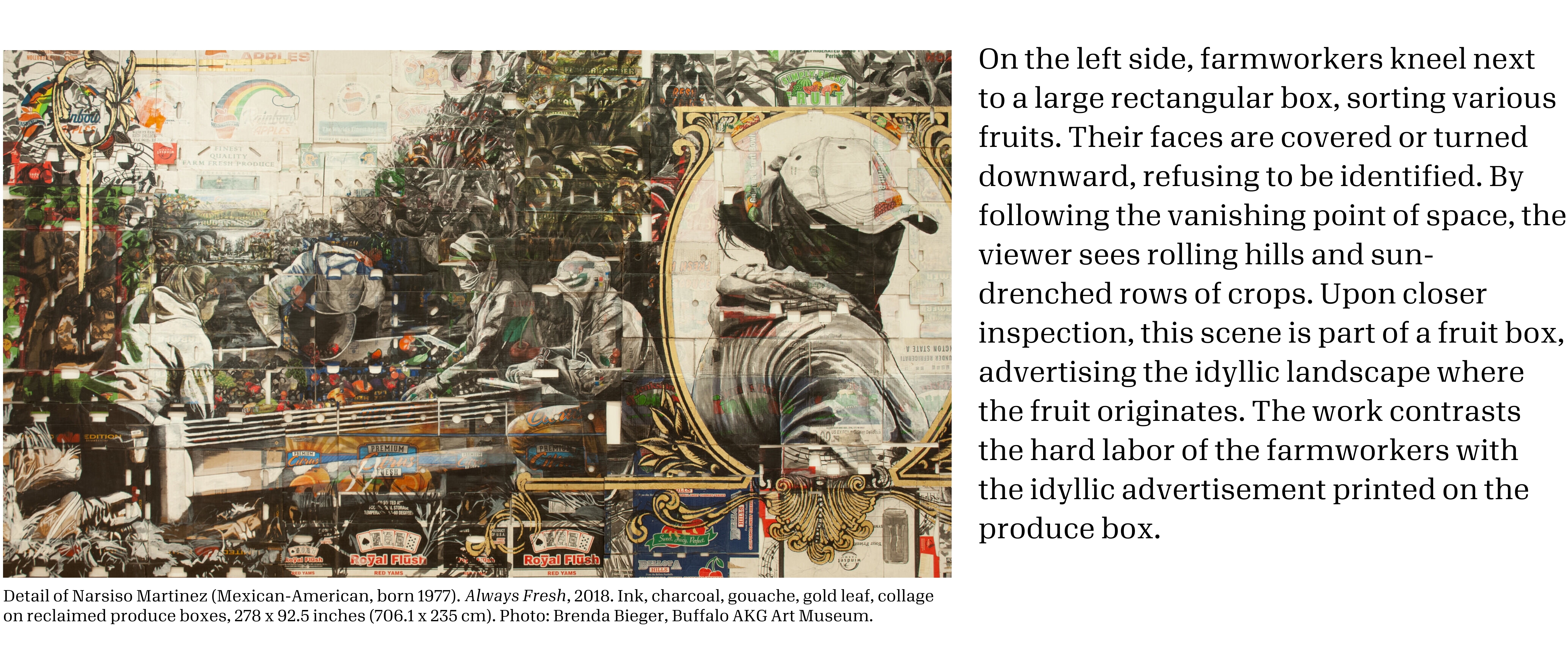

The largest work in the exhibition, Always Fresh, was created by Narsiso Martinez in 2018. Deploying ink, charcoal gouache, and gold leaf onto collected produce boxes, the work depicts three disparate scenes of farmworkers. These representations of fruit harvesting reference a landscape far away from the exhibition site in Buffalo, most likely in eastern Washington, where the artist formerly worked. The cardboard boxes read “California’s Finest Sweet Potatoes & Yams” and “Washington Rainbow Apples.” The work’s materiality emphasizes the notion of geographic distance. As a viewer from Buffalo, it’s easy to feel physically removed from the subject matter. However, this feeling of distance accurately represents our current food system: a system predominantly reliant on distant industrial farms and shrouded migrant labor.

The produce boxes reference commodity objects shipping and circulating, entrenched in our current capitalist system. International trade networks enable vast distances between an object’s production and the consumer. The trade of these commodity objects creates significant waste through packaging and fossil fuel emissions during transportation. These complex trade networks are juxtaposed with the advertisements on the collected box, which read “simple and fresh fruit.” Agribusiness relies on advertisements of bucolic simplicity to make its products appealing to consumers. However, these advertisements contrast with the reality of complicated trade networks and sterile industrial farms.

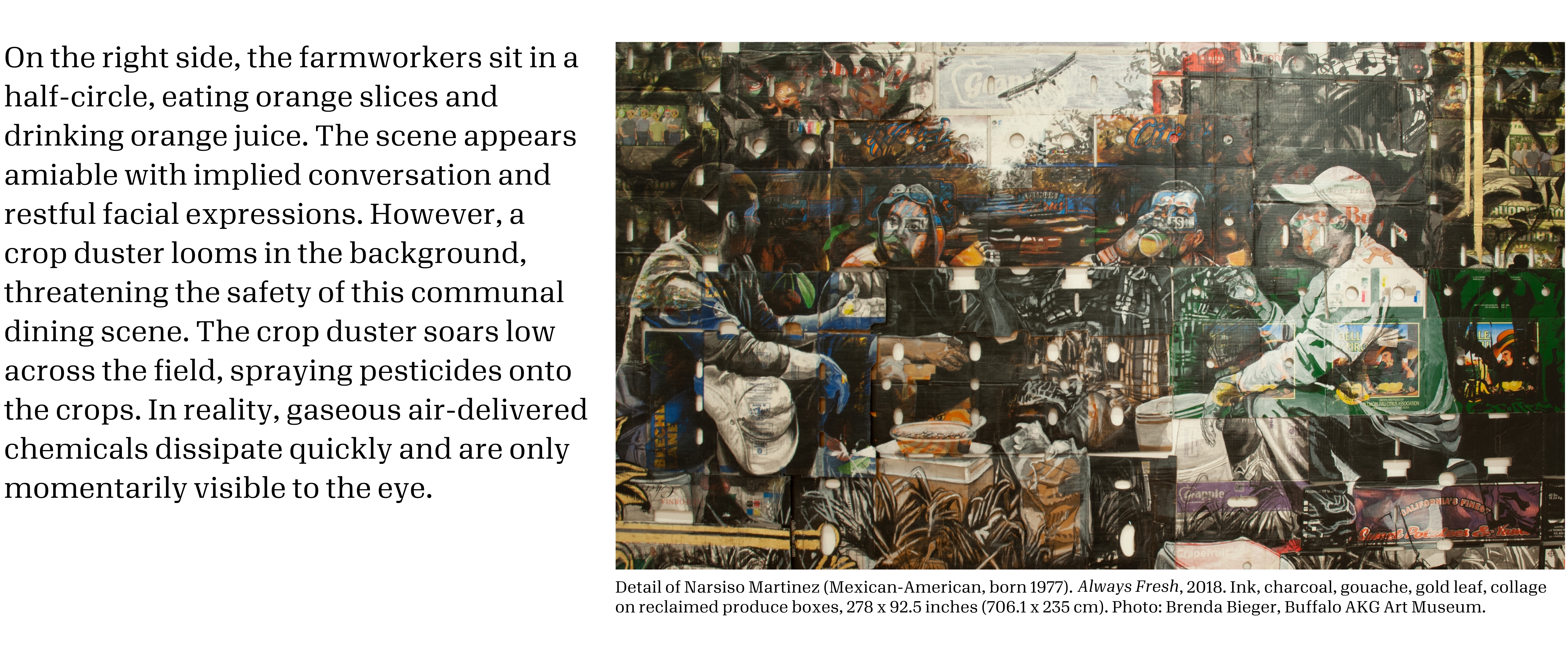

The vanishing points of the two farm scenes in Always Fresh, 2018, depict contrasting images: the pastoral imagery of farming from advertisements and a crop duster spraying toxic chemicals on an otherwise convivial scene.

In Always Fresh, 2018, a bright chalky white color depicts the pesticides, establishing a visual permanence to these chemicals. This white film of toxins coats the plants and farmworkers. By depicting invisible chemical substances, this work emphasizes the permanent traces that pesticides leave on the bodies of farmworkers.

In Always Fresh, 2018, a bright chalky white color depicts the pesticides, establishing a visual permanence to these chemicals. This white film of toxins coats the plants and farmworkers. By depicting invisible chemical substances, this work emphasizes the permanent traces that pesticides leave on the bodies of farmworkers.

The farmworkers cover their mouths and noses, wearing bandanas and facemasks. However, these face coverings provide farmworkers with limited protection from inhaling pesticides. It is well known that occupational exposure to pesticides can cause elevated risks for certain types of cancer and respiratory issues. [8] The farmworkers also wear baseball caps and hoods, shielding their skin from ultraviolet rays. While these coverings principally function as protective gear, they also create tension between visibility and invisibility. In the scenes depicting the farmworkers sorting fruit and the center portrait, the identities of the figures remain concealed. As farmworkers, they often operate from a place of social invisibility, are not widely represented in popular culture, and are systemically disenfranchised. As Martinez states, farmworkers should “not be portrayed as ghosts or something that nobody talks about, but we all benefit from.” [9]

Narsiso Martinez: From These Hands/De Estas Manos sparks dialogue about food systems in the art museum. While sauntering through the gallery, visitors must contend with specific people who underpin America’s food supply. Several of the works depict highly-detailed portraits of farmworkers who make our produce aisle purchases possible. These works are filled with people wearing protective gear and coated in toxic gas forms, highlighting the unsafe working conditions in a food system structured by monetary incentives.

By bringing our distant and opaque food system into startling relief, the exhibition forces the viewer to wonder who grew their oranges, where, and under what conditions.

No longer satisfied with the status quo, Buffalo community members have been advocating for more just food systems. One organization, the Providence Farm Collective, combats transnational forces with local solutions. Providence Farm Collective, located in Orchard Park, helps refugee and immigrant farmers adjust to regional farming practices through land access and business education. Another organization, the Massachusetts Avenue Project, is an urban farm on the East side of Buffalo that “address(es) the growing land vacancy, high youth unemployment, and food security needs of the community.” [10] The Massachusetts Avenue Project is also fostering the Good Food Buffalo Coalition, a group of organizations that advocates for a transparent and equitable food system through the purchasing power of public institutions. Through supporting regional food systems and local community initiatives, Buffalonians have the opportunity to bring proximity and transparency back into their kitchens.

Ava Danieu is a writer from Western New York living in Somerville, Massachusetts. She studied English Literature at Wesleyan University.

Footnotes

- https://regional-institute.buffalo.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/155/2021/12/Reconsidering-Concrete-Atlantis-Buffalo-Grain-Elevators.pdf

- https://www.beaconjournal.com/story/news/2016/10/08/old-grain-elevators-line-buffalo/10491246007/

- Rustbelt Radicalism, 175

- https://www.beaconjournal.com/story/news/2016/10/08/old-grain-elevators-line-buffalo/10491246007/

- Rustbelt Radicalism, 176

- https://www.nytimes.com/2022/11/10/arts/design/narsiso-martinez-farmworkers-artist-california.html

- https://podcasters.spotify.com/pod/show/heidi-zuckerman/episodes/119--Narsiso-Martinez-e26plo1

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7879472/

- https://podcasters.spotify.com/pod/show/heidi-zuckerman/episodes/119--Narsiso-Martinez-e26plo1 41:30

- https://www.mass-ave.org/history