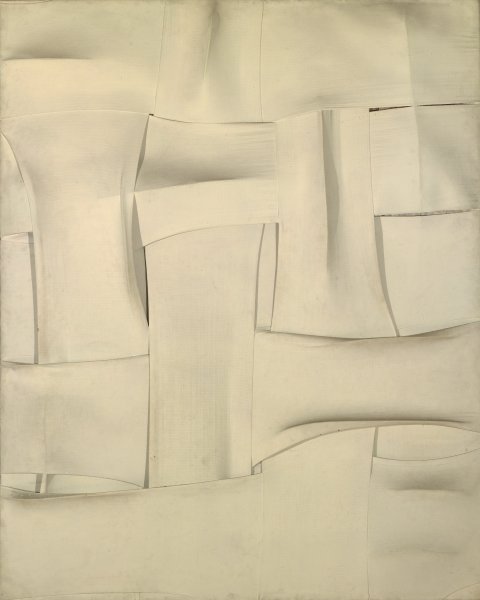

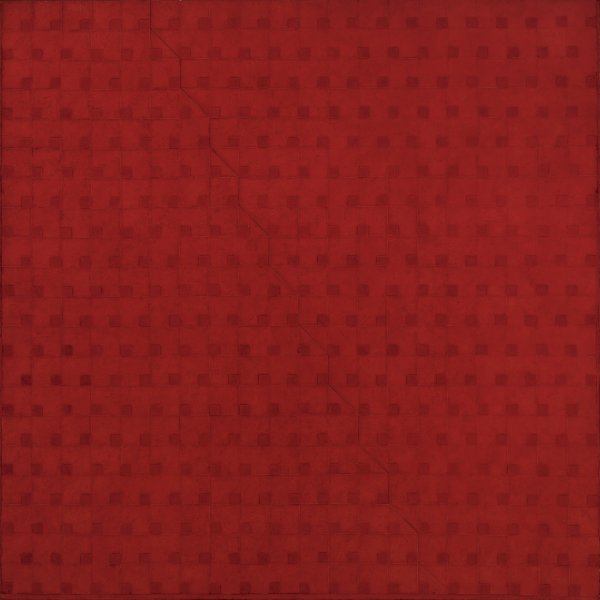

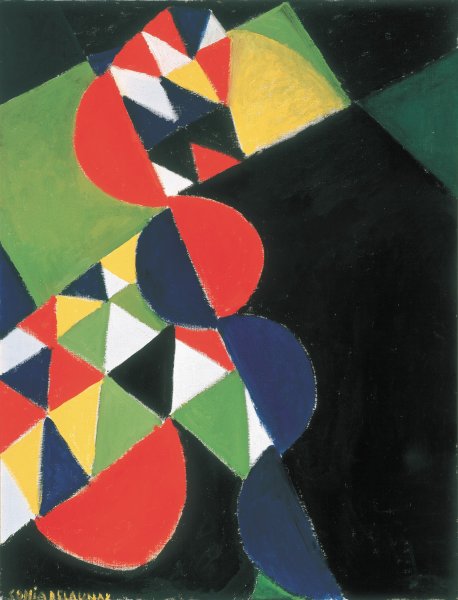

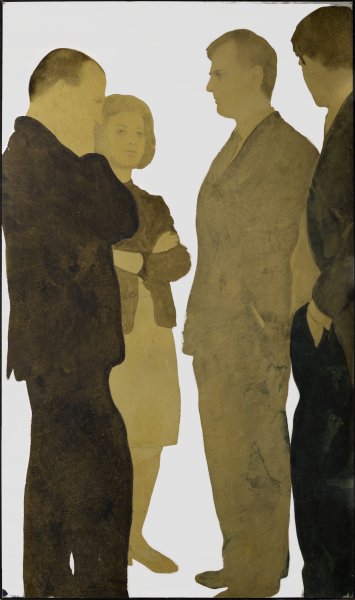

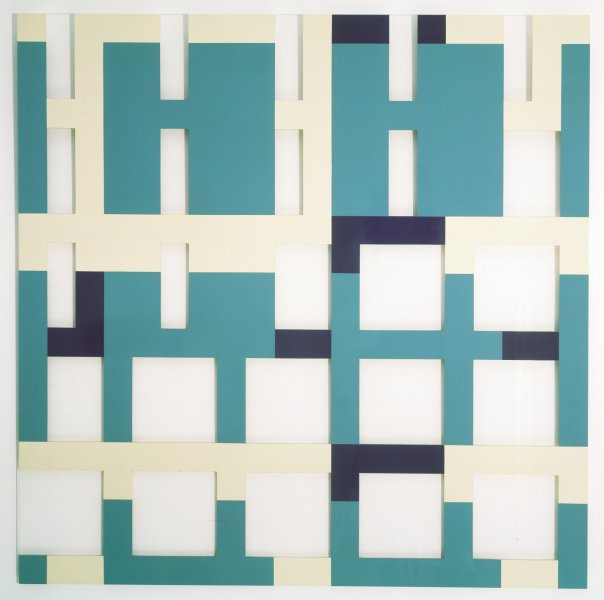

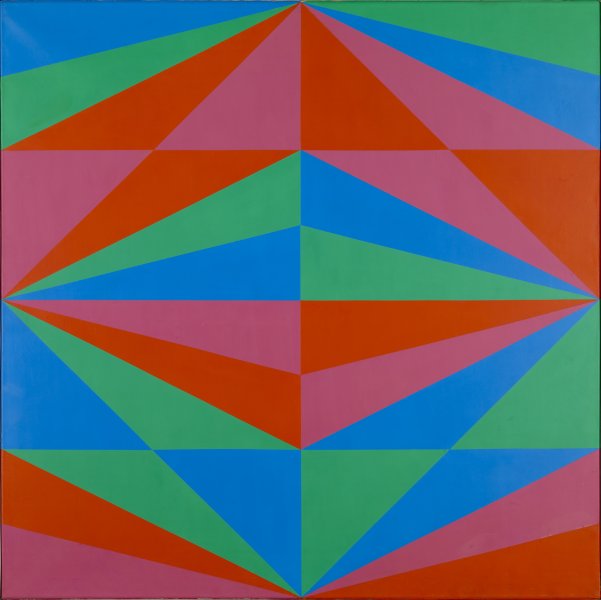

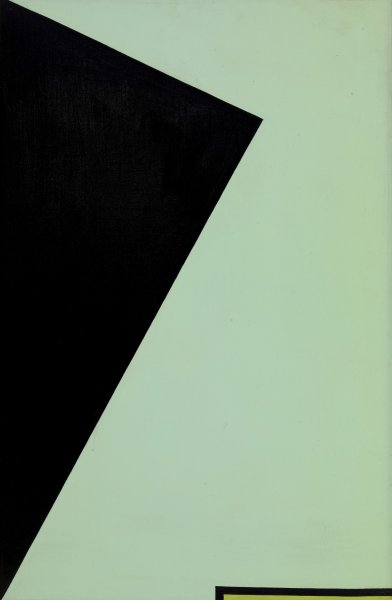

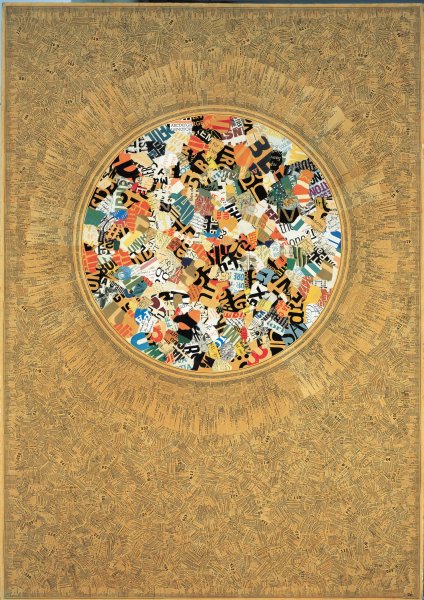

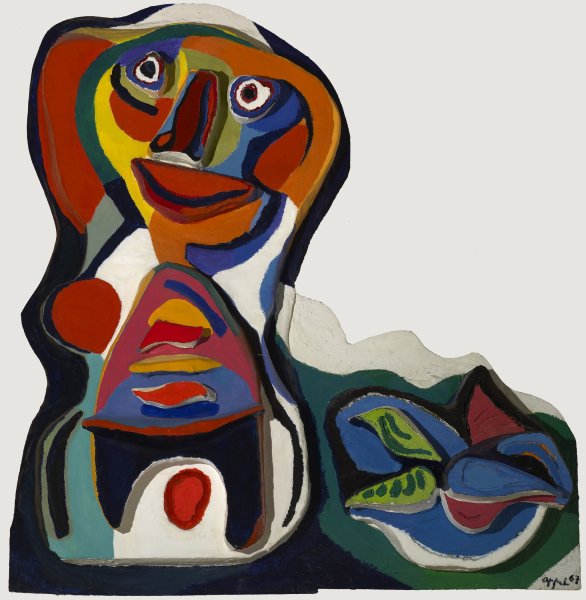

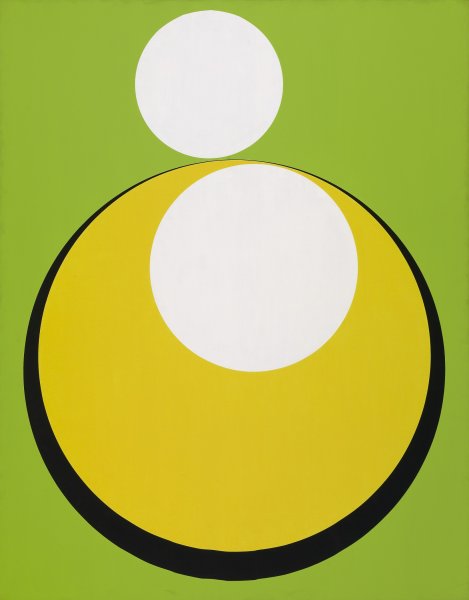

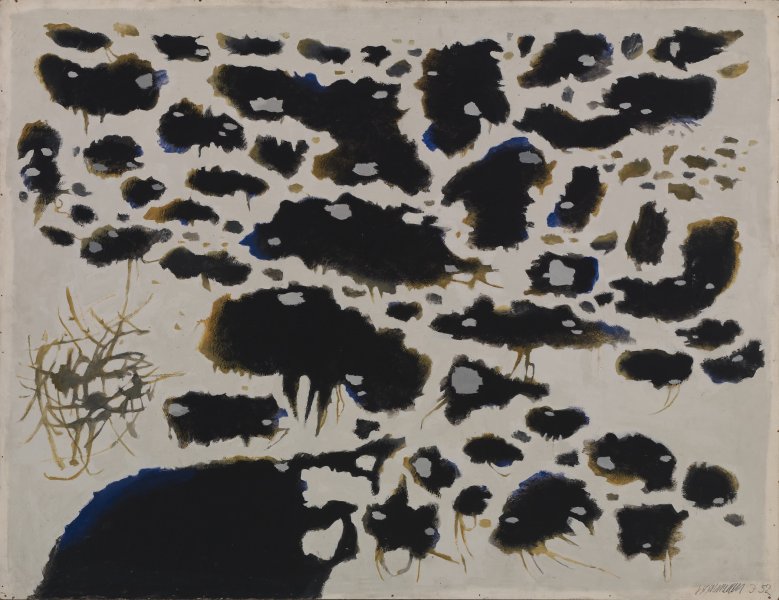

Continental Painting and Sculpture, 1942–72 in the Albright-Knox Art Gallery

Friday, July 21, 1972–Sunday, August 27, 1972

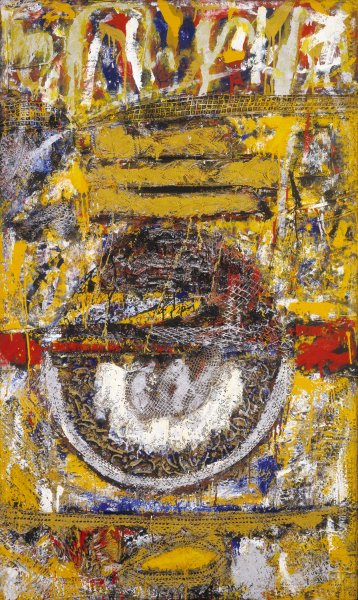

Installation view of Continental Painting and Sculpture, 1942–72 in the Albright-Knox Art Gallery. Image courtesy of the Albright-Knox Art Gallery Digital Assets Collection and Archives, Buffalo, New York.

1905 Building

Continental Painting and Sculpture, 1942–72 in the Albright-Knox Art Gallery was part of a series of special collection-based exhibitions organized in celebration of the tenth anniversary of the opening of the 1962 Building.

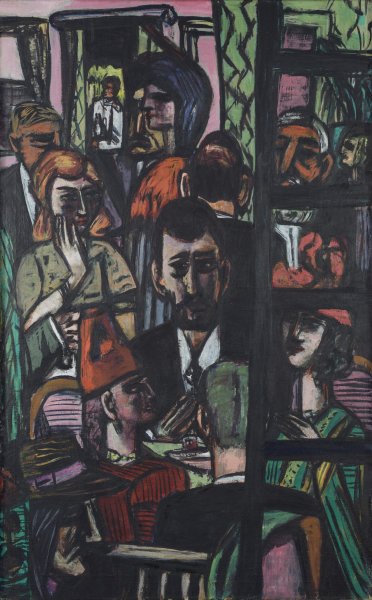

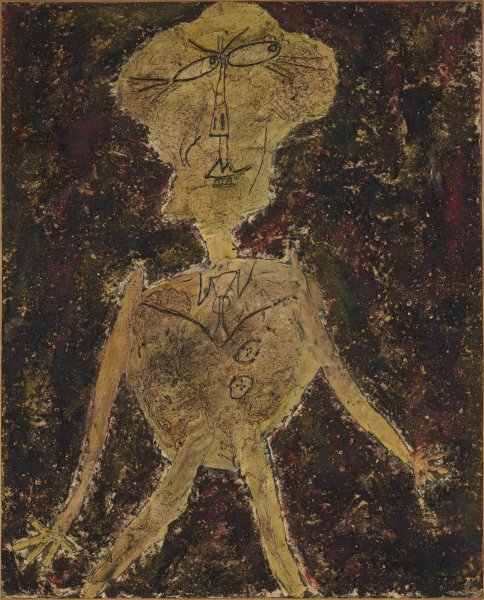

Continental painting since the end of World War II is a complex of individuals and groups, some with international ambitions, others with a sharper sense of local identity. There is, in addition, the fact that the dominance of American art in the period under discussion, has had the effect of reducing American interest in European art.

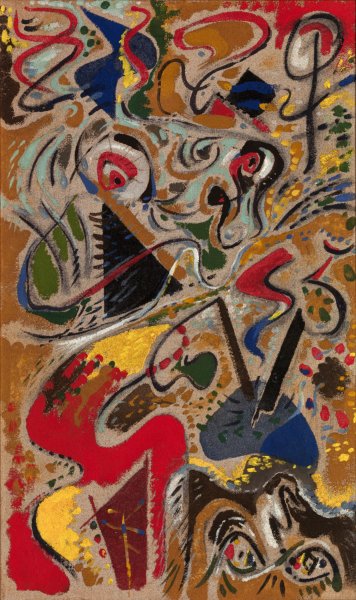

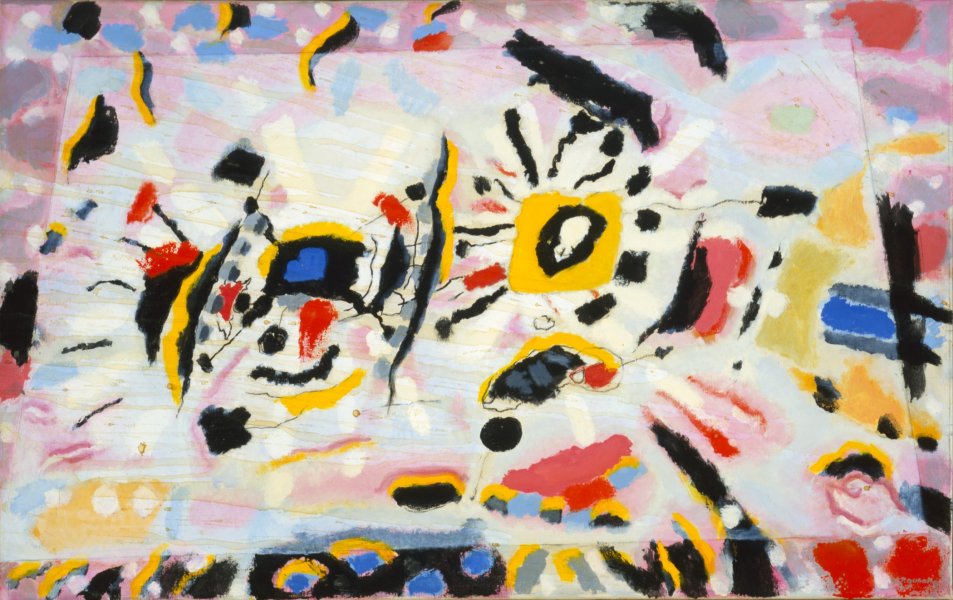

The dominant and unanticipated new factor in postwar painting was a florescence of painterly criteria. Modern art, understood in terms of Cubism and abstract art or in terms of Picasso's basically linear style, had been equated with line and with composition. The tradition of Monet, Bonnard, and Matisse had been relegated to a lower position than the constructive, supposedly classical, main line of modern art. In the late 1940s and 1950s, all this was changed by a reordering of the way in which paintings were produced and in what they looked like when done... As painterliness developed, it followed that color, and the experiences of color without linear boundaries or chiaroscuro, became of prime importance.

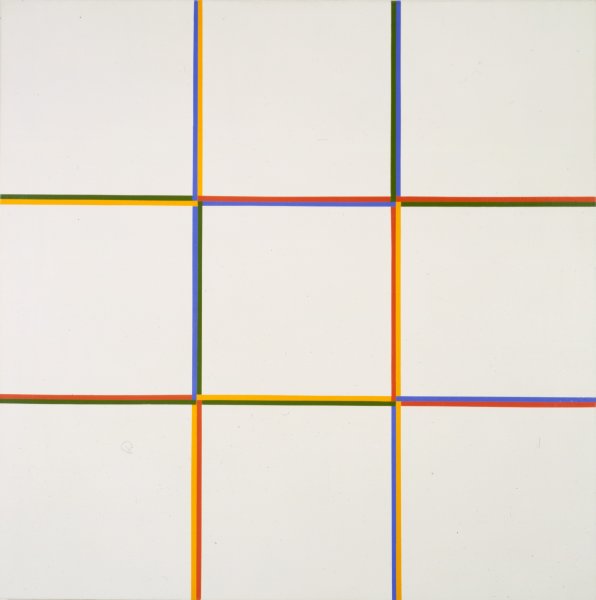

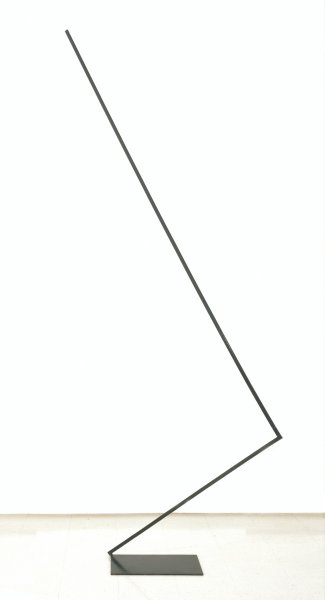

The spread of painterly criteria was not unopposed. One alternative to it was centered in concrete art, defined by Max Bill in these terms: "we call concrete art, those works of art which originate on the basis of means and laws of their own, without external reliance on natural phenomena or any transformation of them." The differences between art as process and art as end-state are irreducible and the two positions were polar opposites among the options facing European artists.

There is a fairly clearcut dividing line in continental sculptures of this period between two main groups, the organic and the inorganic, the warm and the cold, the subjective and the objective sculptors. Within each group, however, endless refinements of divisions and cross-references are possible because of the lack of schools and coherent movements.

Both groups have their roots in the turbulent, formative years of the first quarter of the century. The postwar sculptors, those who had to find their personal style after the war, continued along the lines set out by the older generations from before the war.

In spite of all theories, European sculpture in the 1950s and 1960s remained imprisoned in its own realm and, for the better part, bound to the pedestal. Size and scale usually stay within the limits of human measurements.

This has been a period of almost frantic research, of countless experiments. Everything is possible, every new idea is accepted. This sometimes lends to a desperate search for originality, but also to the discovery of uncharted territory.

Continental Painting and Sculpture was accompanied by a Gallery Collections Catalogue, with essays by Lawrence Alloway and R.W.D. Oxenaar.

This exhibition was organized by the Albright-Knox Art Gallery.

Related Artworks

No image available,

but we’re working on it

No image available,

but we’re working on it

No image available,

but we’re working on it

No image available,

but we’re working on it

No image available,

but we’re working on it

No image available,

but we’re working on it

No image available,

but we’re working on it

No image available,

but we’re working on it